In a couple of hours, I will meet my lifelong musical hero. I have been granted an exclusive half-hour interview with the man whose music has enriched my life – and in more ways than one even saved it. Right now it feels like I am being rewarded for my work. It doesn’t get any bigger or better than this!

So many good memories flash through my mind as the train rolls on. All the way back to the little room where, in the spring of 1965, a five-year-old kid heard The Last Time for the first time. Every record since then – every song, every guitar lick, every drum roll, every lyric – I have loved and cherished them all. I am indebted for life to the Rolling Stones.

This is all happening thanks to my guardian angel in the business, public relations executive Siw Grindaker. She is the one who will shine a light on me and make sure that I get what I need. Siw phoned me in July to inform me that Keith Richards would give one exclusive radio interview for Norwegian radio in connection with his autobiography, and as the book publicist, Siw went into the ring to fight for me. “I just know that Keith will enjoy talking to you!”

The book, “Life”, was translated and sold phenomenally well in Norway – over 40,000 copies in a country with 4 million people. One out of every hundred Norwegians bought the book by the rock music icon who I was journeying to interview.

And to think how it all could have gone wrong: The date was originally Wednesday November 10th, 2010. So I booked a flight and a hotel room. Then came a new message from the management: I was granted an interview on Tuesday the 9th. Oh-oh. This meant rescheduling an expensive flight and hoping the hotel had a vacant room for the night before. They did. I breathed a sigh of relief.

Sometime during October the itinerary for Keith’s stay in Paris was mailed me. My name was there – My name was there! – but now it was listed on Monday the 8th! I phoned Siw: “Is this correct?” “Yes! You’re in!” “Yeah, great, but it’s the wrong date! I have booked and rebooked the flight.” Siw asked me if there was a problem. I told her yes, hung up, phoned my boss who raised my traveling budget – “I really want you to do this,” was his exact words – and then booked a third flight to Paris. And a new hotel, at twice the price as my first choice, which was now full.

Problems out of the way, I phoned Siw and agreed to meet her at Le Meurice hotel an hour before the interview. So far, so good. Nothing could go wrong now. The only thing that could possibly spoil my French experience would be a flight delay. Which of course was exactly what occurred.

The plane that was to take us from Oslo to Paris couldn’t take off due to technical problems! As I sat there and heard the captain telling us they were trying to find another plane, I felt the hand of fate was a bit heavier than expected. After a one-hour delay we boarded a new plane and were finally on our way. At the airport in Paris I ran to the train, sat down beside a young girl who looked like the cover of a magazine and asked her if this was the train to Paris. “I hope so,” she replied. When the train left the station it had two lost souls on board – one headed for a photo session, the other for the interview of his life.

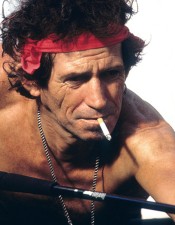

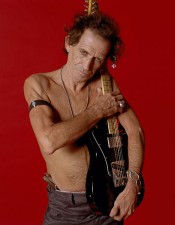

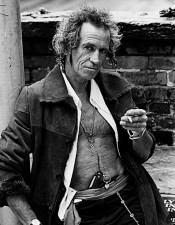

All the problems I may have had on my journey are gone with the wind at the moment Keith Richards enters the room for our appointment at six o’clock on Monday 8th November. I tremble with excitement by the mere presence of the man. He looks great. Younger than on any of the photographs taken the last decade or so. He smiles, almost sheepishly, and shakes my hand. It is a firm handshake, hard and soft at the same time. It makes me feel welcome. “Norway, eh?” he says with a grin.

I admit to him that I’m nervous. “I’m a bit nervous myself!” he says, and that lovingly hoarse laughter rings out. The ice is broken. Keith Richards wants to talk – with me! The next 45 minutes are a joy. The most rewarding interview I have done in my 25 years as a music reporter. The one time in my career when I am certain that I am the luckiest person alive. Keith Richards turns out to be the most charming, polite, open and (I believe) honest rock musician I have ever had the pleasure to meet. And I have met quite a few. I start off by admiring the title of his book. It’s almost like you’re in it for life? “Yes, it is!” But is it a good life? “It’s better than jail!” he snaps back.

After the basic question – “Why did you write a book?” – I started asking him about the things I wanted to know more about. Like for instance the finger he crushed in childhood. He wrote about it in the book, but didn’t tell the reader which finger it was. So which one was it, Keith? “Oh, it’s this one!” he said, showing his right index finger. It has a visible scar and a slight curve. “It’s been deformed since I can remember. Maybe it has had an effect on my guitar playing, because I can do this (snaps fingers on the left hand) but I can’t do this (tries to snap with his right hand). This finger won’t snap! So maybe it has something to do as well in the way I hold the pick and do finger picking.”

Next up was the drug years: “An experiment that went on for too long! I think I was using the stuff basically as a cushion against all the fame and the public attention.

The fame thing is a difficult thing to deal with. Some people get carried away by it, I wanted to hide from it. And my way of hiding was dope.”

We talked about his parents Doris and Bert, about the amazing chemistry in the band, about the ancient form of weaving guitars together, and about Ian Stewart – “It’s his band, really, the Rolling Stones. He used to call Mick golden bollocks!” And then I asked him how he managed to turn every crisis in his life into a great song: “I hadn’t really thought about it that way. But I suppose incidents in life … (pause) … what comes out is a song. (At this he recites a few lines from “Before They Make Me Run”.) Music is, after all, to describe what cannot be put into words. I’m nowhere near as good as I want to be. I’m still looking for a song that will say to me ‘Now I’m really a songwriter!’ You’re always hoping and feeling, and that’s what keeps you going.”

And then – would he talk to me about the more painful parts of his life? He would. “Going back and reliving some of these moments was hard. Probably the hardest bit was the death of my son (Tara, on June 6th 1976). That was the most painful part. Poor little boy. He had no chance.” At this, Keith held his hands as if he held a baby, and went silent for a few seconds. I was uncertain if I had gone too far. But I took a chance and asked him about the recording that the band was scheduled to do in Paris the same night and which ended up on the Love You Live album.

“I had to go on stage, and that was hard as well. At the same time I was happy to go on stage, and I wanted the show to go on forever. I didn’t want it to end, ‘cause then I knew I had to go back and deal with my son’s death. But I had Marlon with me, and that helped. I had to shelter him and become father in the full sense of the word. In a strange way you take a distance from yourself when these sort of things happen. And I did pretty well on stage that night.” Music and Marlon – maybe the two most important things to you right then? “Exactly,” he said quietly.

After 40 minutes – ten more than what was originally agreed – a press agent comes in and says time’s up. I look at Keith: “Can I ask just one more question?” “Sure!” he says, lighting another cigarette as if to signal that he wants to sit and talk for another five minutes. I ask him about what has made him afraid in life. “A few things related to drugs and cars turning over. But really, all of the scary things in life happened so fast that I was only dealing with it then and there. It was only after it happened I woke up and thought ‘Phew! How did I get out of that’? I’ll tell you, when things are really scary you don’t have time to think. You’re just trying to survive. You get a little scared later and sweat it out. Otherwise, nothing’s that scary!” A broad smile and that unmistakable laughter, and the interview is at an end.

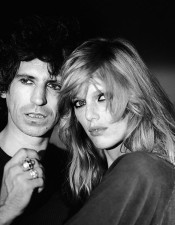

Before he leaves he signs my copy of his book and poses with me as Siw takes a photo. Another handshake, and he’s off. Siw and I hug. We celebrate with a round of beers in the bar. The next morning, as I enter the train bound for the airport, I come to think that I haven’t eaten since I left my hometown Bergen the day before. But I’m not hungry. I’m only happy.

In retrospect, Keith was so real, so human, and now I understand the Rolling Stones even more. I also understand that his renegade image is often exaggerated. The first time I saw the Stones was in Gothenburg, Sweden in 1982 where Keith got a bad rap from the press for being a falling-down drunk, but I know otherwise.

I watched as Keith walked slowly backwards during the solo on Beast of Burden, and then stumbled and fell because he didn’t see one of the steps on stage. In too many books and articles this has been referred to as a drunken stumble and fall, when in fact it was a very innocent accident. And Keith kept on playing, not missing a note. My idol does not disappoint in any way, even up close and personal.

My life as a rock radio journalist was also rewarded by one of my other Stones idols, Charlie Watts. The buzz was all around: Charlie Watts is in town! We had our daily radio shows at the Bergenfest music festival, in front of an audience of 200 people in a hotel bar, and we desperately wanted Charlie to be one of our guests.

This was Tuesday and the next day, Wednesday 28th April 2010, Charlie was scheduled to play with the ABC&D of Boogie Woogie jazz band. The band name is derived from the initials of the first names of its members: pianists Axel Zwingenberger and Ben Waters, with drummer Charlie Watts and bassist Dave Green. They mainly play boogie woogie, but also blues and rock ‘n roll. Suddenly, someone told me that Charlie was in the lobby. I ran out, and sure enough – standing in the lobby was the one and only Charlie Watts. I nearly ran him down from excitement.

He had already been informed of the radio show, and was curious to know where it was and how the room looked. He peeked in through the door and said “This is nice. We’ll do this tomorrow. I’ll bring the band.” I nearly fainted. You mean you’ll play? “Yeah!” The next afternoon Charlie Watts came strolling down a quarter hour before the start of our show, just to make sure the drums were set up. They were. He nodded his approval and went to his room to find proper clothes to perform in.

Imagine the excitement a radio host must have when his favourite drummer is sitting backstage, waiting to be introduced and interviewed. Well, that’s the incredible excitement I felt! The band came on stage, I introduced each member, and felt a moment of nirvana when I yelled out “and on the drums – Charlie Watts!”

The band played a lovely boogie woogie number, the audience jumped for joy, and the moment had come for a short interview. I know Charlie doesn’t like being interviewed – especially not in front of a live audience – so I deliberately started by asking questions to each of the other three members. When I came to bass player Dave Green, who is a childhood friend of Charlie, I noticed that Charlie had risen from his drum stool as if he was restless. Or wanted to talk. I took a chance and turned my microphone in his direction: “Can I ask you a question?” “Yeah, sure!” he replied.

I picked up my copy of his book “Ode to a High Flying Bird” – the children’s book he made about jazzmaster Charlie Parker. His eyes lighted up as he spoke warmly about Parker and the fun he had making the book. “I like to draw. I draw all the hotel beds I sleep in when I’m touring with the Stones.” What about the bed you’re sleeping in tonight, I wondered? “Oh no, I won’t draw that one. This is not a Stones tour.” All those beds – it must be thousands of drawings? “It is!” That would make a great book in itself! At this, Charlie started to laugh: “3000 beds! No, I don’t think so!”

I then wanted him to tell me about his big collection of jazz records. “Is it true you went to record shops every time the Stones toured America?” “Yeah!” he replied. At this, Dave Green burst out laughing and said Charlie only went along with the Stones to the States so he could buy records. “And when he came home, we sat and listened to those records, night after night!” Charlie smiled at the memories.

Time was running, so I asked Charlie if he could play one more number. “No,” he said, deadpanned. “I’ve played what I can. But if the other guys wanna play, I’ll join in.” Only then did I realize that this was part of his humour. Charlie doesn’t rate himself high as a drummer. As his old friend Dave Green said: “Charlie just loves to play. And it’s great to play with him.”

The next day, I ran into Charlie Watts again as he was checking out of the hotel and getting ready to leave. He walked over to me, shook my hand and said “I’ll bring the other band the next time.” Please do, Charlie!

05 Mar 2013

05 Mar 2013