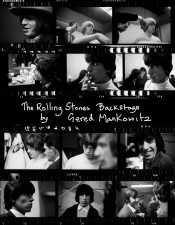

The official photographer for the band in the ‘60s remembers the intimacy.

London in the Swinging Sixties was the center of all things hip, fashionable, sexy and cool, and the Rolling Stones embodied it all through their music and their lifestyle.

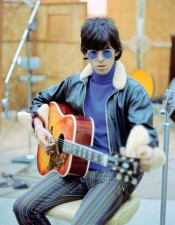

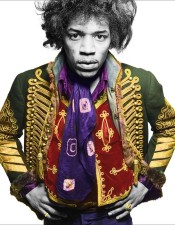

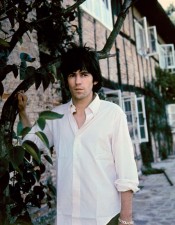

The London sixties was also an era when photos of rock bands and musicians were considered a true art form, and the acclaimed music photographer Gered Mankowitz was an indisputable artist behind the lens. His iconic photos of rock and pop idols, like the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, and Marianne Faithfull, appeared on album covers and record sleeves — and defined the era.

By age 14, he was a photog prodigy, and by 18, Gered became the Stones official photographer at the peak of their original creative success (’65-’67). He went on the road with the band on their tour of America in ’65, which was the fourth time they played in the States in two years.

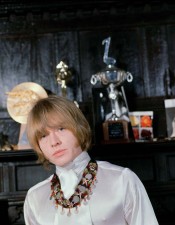

“Those were really the vintage years, when it was Brian Jones’ band — that’s the real Rollin’ Stones”, Gered said. “It’s that initial key period that is so important to their musical legacy.”

Gered got to know the band intimately (and got particularly close to Keith Richards and Charlie Watts), as they began their ascent into the rock ‘n’ roll stratosphere. “I had an incredible opportunity to take photos of the World’s Greatest Rock ‘n’ Roll band as they were emerging, and then found fame,” he noted. “I was very privileged to be there.”

Mankowitz left an indelible mark on the Stones history with his candid portraits. He had unprecedented access and took the band’s photos in the studio, backstage, on stage and off, and he shot them for press and publicity stills. His images of the Rolling Stones appeared on some of their most memorable album covers that are illustrated with striking band photos: “December’s Children (And Everybody’s)”, “Between the Buttons”, “Got Live If You Want It”, and he shot the images inside the package of “Big Hits (High Tides and Green Grass).”

“Back in the day, the album cover was so crucial to the whole experience of how we see our musical heroes,” Gered said in a phone interview from his London office. “So what I tried to do is to shoot everything like it was a cover. I wasn’t trying to consciously create an iconic image.”

However, that’s exactly what he created, and Gered was recently recognized for his iconic photos when awarded the prestigious distinction of a Fellowship to The Royal Photographic Society.

It was during that cusp of the Stones early celebrity that Gered toured with them on their five-week, 36 city tour of America, when the band performed 38 US shows (3 in Canada) from October 29 to December 5. The Stones were supporting their single “Get Off of My Cloud,” which hit number one during the tour.

“They were enjoying the fruits of their fame,” he remembers. “On tour it was just me, the band, their roadie Ian Stewart, who had been part of the original Stones, and their manager Andrew Loog Oldham, when he turned up on a few dates. All-access wasn’t an issue. I was treated just like another Rolling Stone.”

Which did not yet mean the perks of first class hotels, limos or corporate jets, he recalled. “In those days the touring was very amateur, very badly organized. We would rush off after the show, jump into a car and go to the airport. It was the first tour where they had their own plane, which was rather rickety. And we’d usually fly through the night and land somewhere at three or four in the morning and check in to some second-rate hotel.”

Gered downplays his significant role in documenting that early epoch of the band’s history. “I was just an appendage really. I don’t they think there was need for my work, it was not particularly useful as the UK media weren’t interested,” Gered mused. “Yet I had a wonderful time, it was a marvelous experience, but I didn’t want to do it again after that.”

He did, however, reckon that he enjoyed unparalleled access that would not be readily available to rock photographers today. He explained his seeds of success: “The key was to be sensitive to what was going on. I had to have empathy to understand when I could move in and to know when to put my camera away. I had no desire to embarrass or exploit them, just to record the atmosphere and try and capture something of what it was like at the time.

“That sensitivity and trust, that’s what’s really vital to the longevity of my work. Being there at that exact right moment is happenstance, just luck, but what I did to try and stay there, that’s what’s important.”

He noted that he particularly loved shooting the band live. “The best thing, actually, was being on stage with them night after night. I was allowed to be on stage as long as I didn’t get in Mick’s (Jagger) way,” he remembers.

“Mick had a remarkable ability to control audiences, especially on ‘Get off of My Cloud’ and ‘Satisfaction.’ The entire band was incredibly great. I knew I was in the presence of extraordinary talent and gifted musicians.“

Technically, Gered said, the shows were “extremely crude and terribly low key in terms of packaging and presentation and equipment. They didn’t have a lighting show and they didn’t have a proper sound system. They were so raw in so many ways.”

Emotions were also particularly raw with the band’s early founder and leader, Brian Jones, whose slow descent into madness was sadly witnessed by Gered during those initial years.

“When Brian’s mental illness manifested itself, we had no idea what was going on. We had no medical terminology for it, but we knew he had a fractured personality,” he remembers. “And that was clear from the early days.”

It was not evident, however, from the get-go. “In our first session in ‘65, Brian was visually stunning! He looked terrific, and he had the most defined style and more charisma than any of them,” noted Gered. “When Brian was in a good mood, he was a great guy.”

But by the end of ’65, Gered said Brian “was showing signs of his sort of madness, with twists and turns. He was charming one minute, then a monster the next; he was brilliant musically one minute, then pop-eyed a minute later.

“Brian could be very unpleasant, but he didn’t give me a bad time. I backed off and stayed out of his way because I didn’t know how to behave around him.”

On the tour, Brian famously went missing for several days at a time. Gered remembers that Brian jumped out of a limo in Chicago in stopped traffic and ran off. “Basically, we didn’t know what was going on. We didn’t recall any arguments or major tension to set him off. Suddenly he would be going off on a tangent.

“We didn’t understand what was happening,” noted Gered. “He was a very important part of the band and would appear to be in great form. And then something would happen that nobody understood, and he’d go off the deep end. And then he’d get more drunk or stoned and he’d eventually collapse.

“Brian Jones was an extraordinary personality in his own right, but he was not cut out to be a pop star,” he mused. “And I don’t think he could deal with Mick and Keith’s song writing success, really.”

Gered recalled that Stu really maintained the integrity of the band. “I got on very well with him. We were not close friends, but if he felt you were talking straight talk, you were okay. He didn’t suffer fools gladly. Remember, he was part of the earliest lineup of the band until they cut him.”

As their manger, Andrew Loog Oldham was instrumental in shaping the Rolling Stones, Gered noted. “Andrew had a great vision and great character, and he is often misrepresented in many ways,” Gered said.

“He was key to the Stones in that early period, absolutely crucial as manager and producer. He was the one defining the direction that the Rolling Stones image was to go in. He was a visionary, and as a PR and press rep – he had no equal.”

Andrew Loog Oldham was also instrumental in Gered’s own career. They met when the photographer shot Marianne Faithfull for an album sleeve in London’s Salisbury Pub in 1964, just after she had her first hit single “As Tears Go By.” Andrew was her manager too.

Gered was invited by Andrew to meet the Stones, and then hired to shoot a session in early 1965, from which came the album cover for “Out Of Our Heads,” (“December’s Children” in the US), which “was the most important session that I had done up to that point,” he said. “And they all liked my images.”

Their reaction to his work helped soothe the frustration of the Marianne Faithfull session where “my favorite image of her (from the shoot) didn’t get used. There were three guys reflected in the mirror behind her, and I thought they contributed to the sexual dynamic. Although she was modestly dressed, their presence lent a voyeuristic quality and sexual tension.”

The record company chose a much safer version, Gered said, “but it wasn’t nearly as good. The picture I liked stayed in the archives until the ‘90s when interest in my work became serous and intense.”

His archives are filled with photos that were never published, “because photographers had no say over what the record companies would choose,” he said. “Often the bands had no idea if they were going to appear in shots that were black and white or color. They frequently never saw the covers until the album dropped.

There wasn’t a lot of media covering music back then, so the sleeve was often the only visual contact that people had. And it was an incredibly important part of the album experience.

“Maybe there was a kind of purity to that back then. Today millions of kids don’t know what that means. Because of the internet and social media, no mystery remains,” he reflected.

Gered notes that shooting record covers in that decade had its own kind of mysteriousness — it was not an exact science, but it definitely involved skill. “From ’63 on, I shot mostly in black and white because it creates a more dignified and powerful image.

“I used a Hasselblad medium format camera and the image was square, which was perfect because I was always looking for a record cover. The way they came about was random, somebody would discover the picture and say ‘that would make a great cover.’“

His approach to promoting his images was strategic and subliminal. ”I wanted to make sure that everything I shot was perfect for a cover, that the composition had space for the album title and the record label logo.”

His attitude towards a photo session was pragmatic. “I was just focused on trying to create an image. It was important that it was artistic, but it was more important that band wanted to use it to promote themselves. I always measured my work by the how record companies and the band liked it.

“It was a bit of a tight rope, jumping between the artists’ integrity and honesty, and creating a sort of unusual image to represent them the way they really were.”

In the sixties, as Gered tells it, the record companies were dominated by Decca and EMI, with establishment figureheads in charge, businessmen who had little idea about rock ‘n’ roll. “But what they did know is that they wanted a piece of the action,” he said. “And the only way to get it was to work with the people who knew about it, so they listened to Andrew (Loog Oldham) and brought what he was selling. They were buying into something they didn’t like or understand, but it was going to make them money.

“They needed people like Andrew, they needed young entrepreneurs, photographers, designers, hair dressers, all giving their power. The establishment didn’t know how to do it, so they used us. Everybody was embracing youth, nobody was putting up any barriers because of your age.”

When teen-aged Gered Mankowitz shot covers for record labels, he had youthful creativity on his side, along with a maturity beyond his years. He cut his baby teeth on fashion, advertising and news photography in London’s trending and swinging West End, where Gered became a trailblazer in his genre.

“I was one of few people who saw music photography as a career,” he said. “And I always judged my work about how successful it is, some pictures were failures as far as I was concerned. But when I revisited them, these classic images sustained their beauty.”

In the past, the record covers he shot had to fulfill very definite requirements, but Gered remembered exactly when that shifted. “It was the end of 1966, when I shot the ‘Between the Buttons’ album and I felt like I was setting out to create a specific cover. It was my first conceptual cover.”

The Stones’ photographer said that he was consciously trying to get an image of the band that had a vagueness to it; he prepared a home-made filter with Vaseline on a piece of glass and used strange distorted colors to create that “blurry, psychedelic, druggy look. It was my visual way of photographing the LSD experience.”

He shot the “Between the Buttons” cover on North London’s Primrose Hill in the early morning after an all-night recording session at Olympic Studios. “We were all pretty wired, cold and tired. We had piled into Andrew’s Rolls Royce and at the shoot we were all smoking dope and laughed a lot,” he remembers.

Brian was infamously behaving badly, and Gered said that Brian kept turning his head, hiding behind his collar or burying himself in a newspaper. “Brian was in the center of the composition, and in a way, disappearing. He was just not cooperating, and I was worried it was all falling apart. I was really worried about him fucking it up,” he recalled.

“But Andrew said ‘don’t worry about Brain. Whatever he does will contribute to the Rolling Stones. It’s part of of what the Rolling Stones are now.’ Andrew freed me and gave me permission to be creative. He came up with the album title after seeing my photos of the shoot.”

Gered continued working with the Stones as their official photographer until 1967, when the band broke off with Andrew as their manager.

He adapted to the change with no interruption to his career – there were plenty of other rock ‘n’ rollers to photograph. His relationship with a young Jimi Hendrix, was forged at a new artist showcase produced by the Animals bassist, Chas Chandler. It was the means to one of his most memorable photos of the legendary guitarist taken in 1967 at his Mason’s Yard studio. The session resulted in a coffee table book of Gered’s entire Jimi Hendrix archive, which is still in print.

His archives also store noteworthy photos of an impressive roster of musician, including: The Small Faces Elton John, Yardbirds, Traffic, Free, Donovan, the Eurythmics, Kate Bush, Gary Glitter, ABC, Duran Duran, Oasis, among many others.

Gered has recently worked with the Hives, Suzi Quatro and Doyle Bramhall ll. “ I haven’t really changed the way I work, I’m still very much old school,” he said. “It’s me and the subject. I don’t use an assistant. I try to find an intimacy, that closeness, which I communicate from the lens. After fifty years experience it’s the only way I know how to shoot.”

Some of Gered’s staggering 50-year work canon has been reproduced in several books, including “The Rolling Stones,” “I-Contact,” “Mason’s Yard To Primrose Hill,” and it has appeared in many worldwide exhibitions and galleries. His newest exhibition and book feature many exciting, rare – and some unseen – photos from his immense catalog.

“It’s fantastic, absolutely fantastic, that pictures not seen contemporaneously, and with no commercial need for them, are being showcased today. I’m honored to be able to share this work now. I’m out there promoting my work all the time and it’s really wonderful,” the photographer said.

No one understood the Stones fans’ passion at the time, and later it was realized that they wanted so much of their band’s early history. I feel I captured an important part of that.

But he figures he could never reproduce the experience in the current corporate-run, competitive world of rock ‘n’ roll photogs. “Even if asked, I don’t think I could work with the Stones these days. I couldn’t stand the pressure. When I go see them, I buy my own ticket and don’t try to go backstage. I’m not interested in trying to get their attention.

“I was treated like one of the band then, and I know now it’s impossible to recreate that intimacy,” said Gered. “And I wouldn’t want it any other way. “

27 Mar 2016

27 Mar 2016