He’s been an influencer on the rock ‘n’ roll recording scene long before being an influencer was in the zeitgeist as someone who impacts your decisions.

He has produced, engineered and shaped the sound of some of the most influential artists in rock history in legendary recording sessions over four decades.

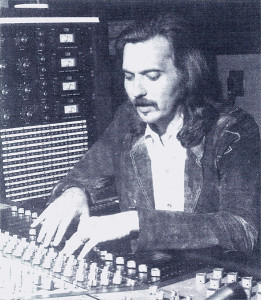

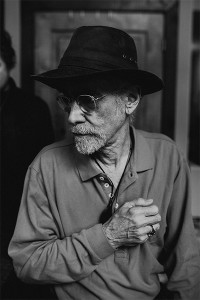

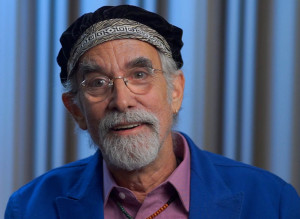

Rob Fraboni is a Sound Master who knows how music sounds and he’s turned many an acclaimed artist’s musical vision into a sonic reality.

It’s in the recording studio where Rob prefers to hang his fedora, even after having been a record label exec with his own boutique label and an inventor of music technology software with speakers named after him.

His discography is a rock ‘n’ roll Who’s Who: He’s worked on over 200 live and studio recording projects with musicians like the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Etta James, U2, The Beach Boys, Joe Cocker and Bonnie Rait.

He even carried some of those relationships out of the studio and into real-life. Rob was Eric Clapton’s best man at his wedding to Pattie Boyd and Bob Dylan invited him to be the sound consultant for the Dylan/Band Tour in ‘74. He’s designed and built recording studios for the Band (Shangri-La) and Chris Blackwell. And he speaks frequently to Mick Fleetwood.

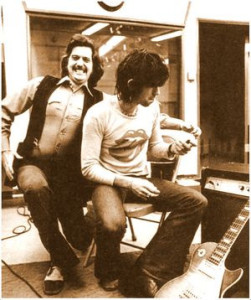

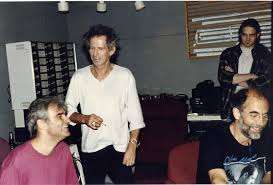

But it is his friendship with Keith Richards that is most notable. It’s also the most musically, professionally and personally satisfying.

Along with Keith, Rob won a Grammy in 2002 as co-producer of “You Win Again,” which Keith performed for the Hank Williams tribute album “Timeless.” He co-produced Keith’s material on “Bridges to Babylon” and his solo project with the Wingless Angels. Keith calls him a “genius” in his autobiography and ‘Mr. Overbearing’ in the studio. And Rob is Keith’s Connecticut neighbor.

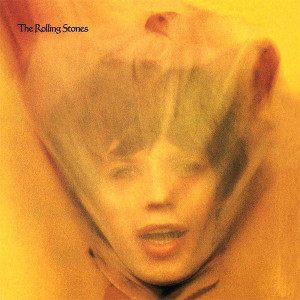

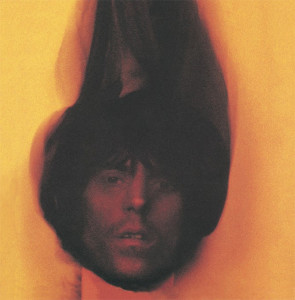

The Keith kismet began when Rob was, at first, a fly on the console for the “Goats Head Soup” sessions in May and June, 1973, at Village Recorder studios in Westwood, California, where he was chief engineer.

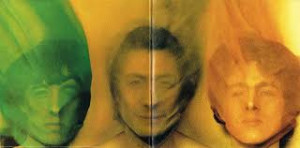

With the recent popular re-issue of “Goats Head Soup” featuring outtakes and new versions of old songs, the Rolling Stones have the distinction of being the first band to chart a number one album across six different decades. Rob was among the first to hear the music.

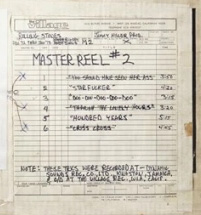

I reached out to Rob about his memories from the album’s creation. I asked about that fateful two weeks when the Stones were at “the Village” and cut seven songs after recording the album in Jamaica. I was curious how he and Keith became friends. And I wondered how his handwriting ended up on the GHS album master tape box.

In this revealing narrative, Rob recalls the album’s decadent history and his own place as a Sound Master in the storied annals of Rolling Stones history.

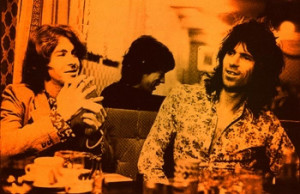

“The Stones had been banned from something like nine countries because of various drug busts and they were looking for a place where they could stay and record a new album for as long as it took. And Jamaica let them in,” Rob told me in a phone interview while quarantining in his home “about a mile from Keith’s” in Connecticut.

“They ended up recording ‘Goats Head Soup,’ and much more, at Kingston’s Dynamic Sound Studios,” he said. “The studio was booked 24/7 for them to record, so when they came with ideas they could lay down tracks anytime.”

The Stones needed to focus on the next album after “Exile on Main Street,” Rob said. They went to Jamaica seeking isolation without distractions, trying to recreate the relaxed, communal environment of the “Exile” sessions in the Villa Nellcôte in the South of France.

For “Goats Head Soup” they were exiles again and in Kingston the band and crew shared an old mansion-turned-hotel, Terra Nova, the family home of Island Records founder Chris Blackwell.

But this time, the recording scene lacked “Exile’s” intimacy and was plagued with personal and equipment problems. Andy Johns, the album’s chief engineer and mixer, was sent ahead to get the primitive studio in Kingston set up to the Stones standards.

But the changes that the studio management promised, like sound screens, a piano and organ, were not ready when he returned with the Stones to record (the equipment and instruments arrived gradually over time). Studio A was in a low, tiny building with an eight track recorder and another room for the band that bassist Bill Wyman described as “claustrophobic.”

The scene was also colored by dark forces (which ostensibly influenced their music), like the escalating heroin addictions of Keith, and others, and the threat of violence in Kingston. The band traveled with armed escorts and Bill Wyman noted that the Stones were protected at the studio behind two large, double gates guarded by a man with a shotgun.

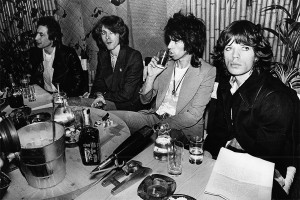

By contrast, when the Stones arrived in late May at Village Recorder Studios, it was a laid-back, accommodating and professional atmosphere in an old Masonic Temple where they could continue to work on “Goats Head Soup.” Rob had been promoted to chief engineer within three months after being hired as a maintenance engineer the year before, and he helped build the Village into one of the top U.S. studios.

“The Stones wanted to work in a studio outside of LA and we were perfect for them,” said Rob. “I was friends with Jimmy Miller and I didn’t know it at the time, of course, that this was the last Stones album he would produce.” Miller was the producer on their previous four albums, “Beggars Banquet,” “Let It Bleed,” “Sticky Fingers,” and “Exile on Main Street,” which are viewed by many fans as some of their best work.

“In two weeks, we cut seven songs on a 2-inch, 16 track. Some were re-cut from Jamaica,” Rob recalls. He noted that the chart-topping “ Angie,” was on a one-inch eight track and cut at Olympic Studios in London where the album was eventually mixed.

“The songs were all over the place and the band came to the Village to turn them into a more focused record, a tighter package,” he said. “It was a darker record in a certain way. ‘Goats Head Soup’ took its energy from ‘Exile’ but seemed in a darker place.

“With time, it has shown to be an incredible piece of work.”

Rob was an eager observer, and then a participant, in a revealing and intimate recording scene in Studio B, which Rob had designed. “I had other studio duties, so I couldn’t be there 100% of the time. Baker Bigsby, a great engineer, was assigned the session.”

Both engineers left their mark, literally. They had a hand in writing the album and song titles on the “Goats Head Soup” master tape #2 box cover. “Yeah, that’s Baker’s and my handwriting,” Rob laughed. “Back then there were no computers to print out song and album titles. We had Sharpies and pencils.”

Rob was an important presence in Studio B that fateful first night in the studio when he and Keith were building their brotherhood.

“It was pretty late that night and everybody split, except Keith. ‘I want to do some bass overdubs’ he told me,” Rob remembered. When Keith plays guitar in open tuning he knows how to deal with the bass to get the sound he wants. So it was basically just Keith and me.”

That after-hours bass session was the start of a rock ‘n’ roll fantasy friendship that’s endured many twists, turns and tweaks some 47 years.

“I had just met him that day and personality-wise we hit it off,” Rob says. “There was nothing to do about it. It just happened.”

His friendship with Keith naturally evolved during the next two weeks of recordings as Rob watched “Goats Head Soup” come together.

The ballad-heavy “Goats Head Soup” was the first Stones album since “Their Satanic Majesties Request” in 1967 to have only original songs and no covers. It was a highly prolific period for songwriting (although “100 Years Ago” was an old tune Mick brought to the session). Critics widely panned the LP and the Stones themselves disparaged it, which Keith would later call “a marking-time album.”

Although they were said to take a lackluster approach to recording, the band was incredibly creative in Jamaica and at the Village. There were so many outtakes from GHS they would end up on other albums including “Tattoo You,” with “Waiting on a Friend” and “Tops.” “Through the Lonely Nights” was the B-side on “It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll (But I Like It)” single and “Short and Curlies” appeared on “It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll” LP.

Rob had a cassette of one legendary, elusive instrumental unfinished outtake, “Windmill” but he noted it was sadly lost in a fire some years later. “There were a lot of great songs from that time.”

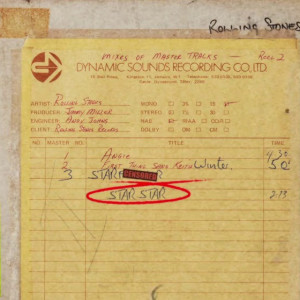

He remembers being especially excited hearing “Heartbreaker” and “Starfucker” for the first time. “Those songs were stand-outs for sure.”

Atlantic Records wanted to exclude “Starfucker” altogether and insisted, at the very least, that the song title be changed to “Star Star.” The album’s release date was delayed by two months because of American anti-pornography laws and the song’s provocative lyrics (for the times).

Mick said in a 1974 interview concerning “Starfucker’s” inclusion on the album that, “I just fought and fought and fought… I can’t bear it all… that finished me. I said, it’s OUR fucking label! In reality it’s not worth it. No, it’s not worth the energy I spent on it and the time, trouble and pressures people try and force on me.”

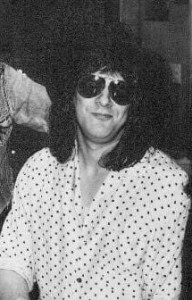

With the controversial “Starfucker” as an emblem, 1973 was an otherwise especially decadent time for Mick. He was jet-setting with his new bride Bianca and at his physique peak. In the video for “Dancing with Mr. D,” Mick’s performance in that skin-tight gold jumpsuit is so hot that I dare any fan who watches it to not get a boner in body, mind or spirit. From rock star to businessman, he was always iconic in so many ways.

“I gotta give Mick a ton of credit in what happened with the Stones, and keeping it together in those days,” Rob says. “He was the driving business force and showed great leadership.”

The music the Stones created in the ‘70’s somehow both eclipsed and embodied the decadence and debauchery of the times. At Village Recorder the antics were mostly contained to one particular vocal booth.

“There was a booth in the back of Studio B where there was lots of partying going on, whatever your pleasure or poison,” Rob recalled. “Mick Taylor, Bobby Keys, Jim Price and Marshall Chess (President of Rolling Stones Records), they were all there. The others, Ian Stewart, Nicky Hopkins, Charlie, Bill, they weren’t seen back there.” Billy Preston was not at the Village, Rob said.

Mick even commented about the debauched scene. “I mean, everyone was using drugs, Keith particularly,” he told Rolling Stone in 1995 and said the ‘70s albums “suffered a bit from all that. General malaise. I think we got a bit carried away with our own popularity and so on. It was a bit of a holiday period (laughs). I mean, we cared, but we didn’t care as much as we had. “

Not many were spared from the effects of the malaise or the drugs. Engineer Andy Johns “was not in great shape, so they left him behind in Jamaica,” Rob said. Regarding those drug-haze days, the late Johns was quoted saying: “Because of drug habits, those sessions weren’t quite as much fun. And there are a couple of examples on there where just the basic tracks we kept weren’t really up to standard. People were accepting things perhaps that weren’t up to standard because they were a little higher than normal.”

Rob concurs. “When you are really high, your hearing is messed up, you hear things differently. So not everyone was at the top of their game. I adored Jimmy Miller but he was out there at this point. The console had a Formica panel and he’d just spend hours doing drawings on it with a grease pencil. I was a bit disappointed, I was such a fan of his.

“Jimmy was a ‘feel producer,’ his guidance was good when he was more active in earlier records. He made so many great records with them, but at this point the Stones are the Stones and they might feel they don’t need somebody telling them what to do. His addiction made him expendable.”

When it came to Jimmy Miller producing the Stones music, Keith said in an interview, “Jimmy Miller went in a lion and came out a lamb. We wore him out completely… Jimmy was great, but the more successful he became the more he got like Brian… He ended up carving swastikas into the wooden console at Island Studios. It took him three months to carve a swastika. Meanwhile, Mick and I finished up ‘Goats Head Soup.’”

Rob explained that when it came to Keith’s remarkable constitution (which has spawned many a meme) it could not be compared to the other partiers in the Studio B booth, because Keith “has a governor. Keith had a boundary and people who tried to emulate him didn’t have that governor.”

Rob went on to note from his vantage point that Keith has been misunderstood and misinterpreted throughout his career.

“Keith plays a role. It’s more of a perception, more of a mythical image of him,” Rob states. “He’s supposed to be a pirate, an outlaw. He’s not really that guy. I never saw that behavior even once. He’s a guy who reads a book a week. Keith’s got a lot of subtleties.

“He’s a sensitive guy and the more sensitive you are, the more numb you want to be,” he said. “That’s how many artists handled their fame when it got to be overwhelming. Look at Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Jerry Garcia, et cetera.“

It was in the strangest of ways, Rob’s connection to Keith carried on with a fateful encounter the day after the “Goats Head Soup” sessions began at the Village.

“I may never have seen any of the Rolling Stones again after that, except for Joe Cocker’s road manager, Mark Aglietti, my good friend,” Rob recalled. “I wanted to get a bite to eat the next afternoon after that first session. We went to Musso and Frank’s on Hollywood Boulevard, where my uncle had worked for 40 years.

“When I walked in, there was Keith Richards sitting in the second booth on the left.” Neither could believe the randomness.

“What are you doing here?” Keith asked Rob. “No, what are you doing here?” Rob asked Keith, and then told him how he’d been coming there his whole life.”

“Sit down!” Keith invited Rob for lunch. “I love this place.”

The crazy Keith connection continued in Jamaica some months later when Rob went on his first trip outside of the US in early August. Mark Aglietti invited him to stay at his rented villa, Green Shade, which was right next door to Casa Joya where Keith and Anita Pallenberg were staying in Mammee Bay.

“Keith knew I was coming but I didn’t know he was there. I walked into Casa Joya and was so surprised I asked him, ‘what are you doing here?’”

And Keith retorted, “what are you doing here?’”

Jamaica had a strong influence on Keith and in his autobiography, Life, he described his time spent there with “Goats Head Soup”: “Our way of doing things changed while we were recording it, and slowly I became more and more Jamaican, to the point where I didn’t leave.”

Keith and Rob would work together some 23 years later in Ocho Rios where Keith bought a mountain-top home, “Point of View,” in the mid ‘70s (and invited Rob to check it out pre-sale). But it was that first Jamaican meet up where Keith would help Rob spread his traveling wings even further and flew him to Paris and London soon after.

“We were at Mammee Bay for five days when Keith had to fly to London. He told Mark and me ‘look after Anita. She gets in rows with police.’ Sure enough she got pulled over and searched and threw a bag of pot in the cop’s face. Mark bailed her out,” Rob remembered.

“Keith told me to meet him in Paris in two weeks, which was incredible. I had never been anywhere outside of the US besides Jamaica. We were there a few days, and then flew to London. Marshall Chess was there too.”

After the rock star treatment, Rob went back to his day job at the Village Recorder, and stayed in loose touch with Keith.

During a studio session with Rick Danko, Richard Manual and Levon Helm of the Band, Keith called and asked, “want come to Toronto with me? I’ve scored a plane!”

So Rob traveled again in rock star style to the legendary benefit Concert for the Blind in Canada on April 22, 1979 at the Oshawa Civic Auditorium. It was the one stipulation of a suspended sentence for Keith’s 1977 heroin conviction in Canada. That show was one of many more special events where Rob could co-exist in Keith’s stratosphere and deepen their friendship. In 1991, Rob became Keith’s neighbor because “he thought we should be neighbors,” Rob said. “Gladly.”

Rob also influenced the choice of one iconic Rolling Stones song and lost out on the personal satisfaction of another.

“One night Keith and I were listening to “Claudine” because the Stones were thinking of putting it out on a compilation album,” Rob said. (The song was included in the deluxe anniversary edition of “Some Girls” in November, 2011.)

“There were two different versions, and I told Keith, ‘the one I have at home is incredible, it’s a better version.’” Rob said that when he played Keith the cassette of the alternate “Claudine,” Keith exclaimed, “This is fucking great!”

“But the one they put out (on the re-release) is the crappy one. I don’t know why the better one didn’t get out,” Rob lamented.

But like an Easter Egg in a video game, there was a hidden surprise. As the cassette kept playing a remarkable song, which Keith had forgotten about, was revealed.

“The reggae versions of ‘Start Me Up’ from the ‘Some Girls’ sessions at Pathé Marconi came on, and then another version came on. And as the last track on the tape played, Keith said, ‘Oh my God, listen to that!’” Rob remembered. “And that’s how ‘Start Me Up’ ended up on ‘Tattoo You.’”

The Keith connection yielded many Sound Master opportunities for Rob. After the “Voodoo Lounge” tour ended in August ‘95, Keith, Patti, Rob and his wife Louise had dinner the next month at the Fraboni’s in Connecticut, where Keith said, “We’re going to Jamaica, why don’t you guys all come? Let’s have Thanksgiving down there.”

When Rob landed in Montego Bay two months later, he called Keith who told him, “well, the good news is you’re here, the bad news is you’re not here on holiday!

“We’ve got ‘The Boys’ back together.”

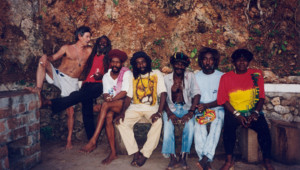

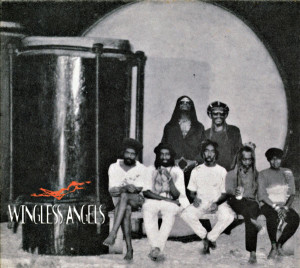

They were going to record the Wingless Angels, the Rastafarian musicians whom Keith first took up with when he bought the home overlooking the beach down from Steer Town.

They had no real band moniker and Keith christened them with their name at the ’95 reunion and quipped that, “their wings were stuck in customs.” The surviving members were back together for the first time in over two decades and this was a once-in-a-lifetime recording opportunity. “Wingless Angels” was eventually released on Mindless Records, an imprint of Island Records.

At Keith’s house, Rob and Keith produced the only Nyahbinghi recordings ever made outdoors. “It’s spiritual music that is only played outdoors,” Rob said. “It goes on all day and night and builds on itself, with musicians stepping in and out like a tag team. Think Parliament Funkadelic.”

The ancient sounds are Rasta chants and songs of praise with dominant drum rhythms, which inspired reggae music but have rarely been recorded themselves. Says Rob, “As Paul McGuiness (long-time U2 former manager) pointed out, ‘if there’s Jamaica Folk Music, this is it.’”

The authentic Nyahbinghi drums the Wingless Angels played on the record had been cured in storage for 20 years. Keith had them made by a Rasta drum maker in Jamaica in the ‘70s but they couldn’t be used until the sound was ready, and that takes decades, Rob said. “And Keith played acoustic, you can hear him wafting in and out on guitar.”

He explained that Keith’s living room opened out to a veranda where the make-shift recording studio was a “simple set-up. I was trying to figure out where to put the mics. We only had five microphones and I had to figure out how to make this thing work. Five mics but only four stands, so I taped one to a telescope,” Rob said.

“I used a hot-rodded A-DAT (multi-track digital audio tape) machine and then transferred the music to Pro Tools to edit, then transferred it to 2-inch tape at Ambient Studios in Stamford, Connecticut.” Several musicians came in for over dubs, including singer Blondie Chaplin, who would later go on to tour with the Stones. Irish multi-instrumentalist Frankie Gavin played the fiddle, tin whistle, accordion and flute on “Wingless Angels.” He also appeared on the “Voodoo Lounge” LP and performed with Ronnie Wood. “Frankie’s from the Highlands, the hills, like the Rastas,” Rob noted. The late singer Babi Floyd, who toured with Keith’s X-Pensive Winos and was a celebrated composer with Sesame Street songs to his credit, was also “an integral part of the recording,” Rob said.

Keith said in Life that Rob helped him find an audio pathway out of the technological nightmare that the Wingless Angels recording had become. In order to preserve the natural flow of the music, the taping had to be non-intrusive and stripped-down.

“Rob Fraboni is a genius when you want to record things outside the usual frame. His knowledge and his ability to record in the most unusual places are breathtaking.” Keith wrote. “Like all geniuses, he can be a pain in the arse, but it goes with the badge.”

It doesn’t seem possible, but the tight friendship with Keith through the years had a down side. It became rather a disadvantage for Rob with the Stones organization and with Mick in particular.

“Mick perceived me as being in Keith’s ‘camp,’” Rob explained about the two main inner circles within the Stones, Keith’s “people” or “camp” vs. Mick’s, which can include assistants, managers, roadies, colleagues, friends and various entourage.

“I got along fine with Mick during ‘Goats Head Soup’ but over time he began to look at me as a foe instead of as a friend of the band. I heard that anytime the possibility of my involvement came up, Mick put the kibosh on it,” Rob said.

When “Bridges to Babylon” began production, “Mick was bringing in different producers, like the Dust Brothers, and Keith told him, ‘I’m bringing in Rob.’”

Rob co-produced three songs for Keith, “which is unheard of, there were never three Keith songs on a Stones album before.”

And the Fraboni affect continued. “(Producer) Don Was asked me to use the mics and setup Keith and I used for the stuff that he was going to record,” Rob said. ”Once the record was finally completed, I went on tour as their sound consultant on ‘Bridges to Babylon.’”

Besides influencing the sound of the album and the tour in the late ‘90s, Rob had a distanced hand in the incredible way the Stones were sounding on their last several tours with the clean, clear, upfront guitar mix.

“I threw front of house engineer Dave Natale’s name into the hat. Among other great gigs, he was Lenny Kravitz’s front of house mixer, and the Stones were smart enough to hire him,” Rob said. “From that point forward, the sound’s been great.”

Although working with the Rolling Stones puts him in a very unique category as a Sound Master, Rob Fraboni is an artist in his own right. He turns simple musical sounds into complex tracks as he connects the junction between analogue and digital engineering with the human ear.

Rob has developed proprietary RealFeel software that “makes digital feel like analog.” He believes that the effect of digital audio on music is “the antithesis of where rock ‘n’ roll lives emotionally.” Rob was motivated to develop a technology “that makes music listenable again, because I’ve found it very difficult to listen to CDs. This fixes all that. It really feels like you’re listening to an analogue record. The other great thing that happens with RealFeel is that even MP3 files feel better than a CD, which seems impossible, but it’s true.”

Rob’s professional accomplishments with other artists are extraordinary. He remastered all of Bob Marley’s catalog for CD on Tuff Gong in 1989 and helped remaster U2’s “Joshua Tree.” At Village Recorder, he engineered part of the Beach Boys “Holland” album, and co-produced the haunting “Sail On Sailor.” He worked with Bob Dylan (and the Band) on “Planet Waves,” did “You Are So Beautiful” with Joe Cocker, “Goat’s Head Soup” and “No Reason To Cry” with Eric Clapton. All within a 21-month period.

He went on to produce the soundtrack on Martin Scorsese’s groundbreaking concert movie, “The Last Waltz.” The three-record live recording of the concert was mixed at Shangri-La as was the first commercial release of “The Basement Tapes” recordings. “The Last Waltz” movie was mixed at Goldwyn Studios. Any additional mixing was done at Village Recorder.

His CV is bursting with so many bragging rights. Rob was executive producer of Melissa Etheridge’s first solo effort for Island Records. He was designer and owner of Shangri-La Studios in Malibu. He’s worked with Patti LaBelle & the Bluebelles and Robert Palmer; produced Buckwheat Zydeco, and John Martyn and signed Etta James to Island.

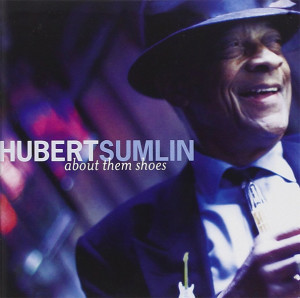

Rob launched his own label (Domino Records) in 2003. They released a fine Rusty Kershaw record with Neil Young, John Mooney’s Testimony, Cowboy Mouth’s first record and an Alvin Lee record. He produced and conceived “About Them Shoes,” the John Handy Award-winning Hubert Sumlin recording, which features Clapton, Keith, and others and was nominated for a Grammy. The label also has music by Nick Tremulis, Sir Mack Rice, Sean Walshe, and Blondie Chaplin, among many others. He’s worked with so many incredibly astute performers.

Not bad for a kid from southern California. His Italian family roots were tapped with accomplished musicians and he was just a tween himself when he became a drummer in a local band at age 11. By the time he was 15, he had many of his own home recordings and he began hitchhiking to Hollywood with his cache. Rob would go in the back door of Gold Star Recording and watch sessions with the infamous Phil Spector, The Beach Boys and Buffalo Springfield, among other legends.

“I was young, eager and got lucky. I had a lot of electronics experience and started out as a musician. Early on I found my career. Or maybe it found me,” Rob wondered.

“And then I realized I was making my living at my hobby and making contributions of some significance! I got my wish — to leave something behind.”

09 Nov 2020

09 Nov 2020